If you’ve ever wondered what it’s like to live in a Transylvanian village in Romania, I have some great news for you – an amazing and in depth guide follows!

You will find everything you need to know about village life in Romania, from how to actually find a home in Transylvania, to how transportation works in these hard to get places, the cost of living and much, much more.

The article below comes from Angela from the UK, who spent 3 months in a Romanian village during the summer.

She really enjoyed her stay there (proving that I might be wrong when saying that living in a Romanian village might not be for you) and decided to help those who are considering a move with all the info they need.

The truth is that there is indeed very little information about living in a village in Transylvania – and even less so when it comes to first hand experiences, so Angela’s article is probably the best resource you can find online on the matter.

So let’s check her article below – I’ll only be back with a few extra words at the end.

Living in a village in Transylvanian

We’re an older husband and wife couple living in Britain where we both work as academics.

In the summer of 2019, we went to Romania and lived in a house in a small village in Transylvania for three months.

We fell in love with the countryside of Transylvania: the rolling hills, the forests, the pristine nature, the views, the small villages, the kind neighbors, and the quiet, rural life.

Villages in Transylvania

There are a handful of villages in Transylvania which have become well-known for tourists in the last decade, like Biertan, Saschiz, Viscri or Copșa Mare.

There are also towns near Brașov such as Poiana Brașov, Bușteni and Prejmer, towns near Sibiu such as Rășinari, Cisnădie / Cisnădioara, and Gura Râului, plus a few others.

But there are a few hundred other villages scattered about in Transylvania which have no tourist infrastructure, yet are often quite lovely for the nature, the quiet, rural life, and the Saxon/Székely architecture.

First, about the tourist towns. The touristic villages have seen a boom in accommodation options in the last few years, and the growth is accelerating.

There are now boutique hotels, rustic manors restored with “authentic” architecture and settings, and many standard guesthouses. You can rent castles (like this one here), schools, religious buildings, and royal palaces.

Some of the areas, particularly the towns closest to Brașov and Sibiu, offer outdoor experiences for both local and foreign tourists: skiing near Brașov, hiking near Sibiu.

But in the other touristic villages of Transylvania, we found that accommodation is geared towards foreigners looking to try a taste of unspoiled European village life but while living with modern amenities.

Typical foreigners seem to be Germans (drawn by the Saxon heritage and architecture, as well as quite a few who have family roots in the area) and British (they like the horse riding, the literary romanticism of the quaint village scenery, plus the Transylvanian connection to Prince Charles), but there are visitors from many other countries as well.

Prices in accommodation focused on foreigners are 60-90 eur per night for a room, with a surprising number costing 150-200 eur. Meals are typically offered at 20-40 eur per person.

Some of the low- and mid-tier tourist offerings such as pensions are owned by locals, but at least from what we saw, most of the higher-end places are foreign-owned (German, Hungarian, Italian).

Several places are owned by formerly-royal families whose properties were taken during communism and then restored in the 1990s and 2000s.

We realized quickly that these towns aren’t for us. Don’t get me wrong: despite the tourist development, the towns are not spoiled.

The villages are real – even extremely well-known tourist villages such as Biertan and Saschiz have long-standing, close-knit local communities – and they’re still very far from becoming a tourist trap along the lines of, say, Mostar or, heaven forbid, Dubrovnik.

The vast majority of tourists in these Transylvanian villages are day-trippers who stay in the bigger cities, so there aren’t enough overnight visitors yet to destroy the character.

But the negative effects of modern tourism are slowly creeping in and increasingly visible, prices have risen, and locals have become a bit mercenary. So all in all, we preferred to stay away from these places.

But outside the centers of the handful of these well-known touristic villages, Transylvania truly is a different and wonderful world: quiet, rural, slow-paced, and under-developed.

Although the tourist towns get the attention, the architecture in many of the other villages is often just as beautiful with the same style Saxon homes and fortified churches (in fact, while the more famous tourist towns see thousands of visitors, dozens of remote villages have churches which are quite incredible but which are visited by almost no tourists).

There’s not a lot of short-term accommodation in the non-touristic Transylvanian villages.

A few villages have a tiny pension/guesthouse, often just a room or two in someone’s home, and in two villages we saw, the local priest offers a room for rent in his home.

Places like these are usually not listed online, so if you’re determined to base yourself short-term in a village, just go and start asking around to find one.

Otherwise, we’d say that your best option when starting out is to use short-term accommodation in a city as your base while you search in the villages for a house for longer- term.

The main cities in Transylvania are quite spread out from each other, with the villages mostly located inside the perimeter formed by the roads between the cities.

So it’s probably best to pick as your base whichever city is closest to the area you’re interested in.

The amount of accommodation available varies widely between the cities. As the main cities and tourist centers, Sibiu and Brașov have many accommodation options spanning a wide range of budgets.

Cluj has a bit fewer but still enough to find something to fit most budgets. Because of its tourist appeal, Sighișoara has an enormous number of pensions relative to its fairly small population and can be a good base.

As a rough guide to prices, we found that a room in someone’s house in a city costs 15-25 eur per night, pensions in the cities cost around 20-35 eur for a room, mid-range hotels 30-60 eur, and fancier places 60-125 eur.

Most places in the cities are listed online on booking.com, Airbnb, and other sites, although we found that we could get better prices by just showing up and paying the owner directly in cash.

Finding a home to rent in a Transylvanian village

This is quite an adventure. The lack of development and infrastructure in the less well-known villages makes the experience both wonderful and difficult at the same time.

We explored Transylvania for two weeks before settling. We wanted to really know several villages well enough to understand the area in order to make a good decision about where we wanted to live for three months.

We found many architecturally glorious houses for rent, many Saxon (German) homes and a handful of Székely (Hungarian) as well. But they often had no running water, no electricity, and/or no indoor bathroom.

In some cases, the homes were owned by Germans who left in 1989 or the early 1990s; the homes were then given/sold to local residents (often Romani), but haven’t been maintained in the years since and are in bad conditions.

In other cases, two or three houses had been combined to form one large home, but then the owner ran out of money and the interior was left in neglect as a half-completed construction site.

We also saw beautiful family farmhouses which had been abandoned and are now used for sheep or cows.

In addition to the traditional homes, many villages have several newly-constructed houses; there’s controversy about the aesthetics of these new homes and the cheap materials they use, since it’s a jarring contrast to the traditional architecture.

But aesthetics aside, many of the new homes are only half-finished because of lack of money, the owner’s need to work abroad, and/or tax issues (the owner can avoid taxes by leaving the home not fully constructed).

We also visited quite a few “modern palaces,” flashy homes built with attention-grabbing mirrored turrets and towers, a style in the villages favored by certain Romani who can afford to show off.

Road access is a big issue to consider. Although almost every village has some form of road access, many are difficult to reach.

The only access roads might be gravel paths, dirt trails, or tire-worn grooves through fields, and rain or snow can make it particularly hard to pass.

On the other hand, we were surprised to find that road access which is very direct can also have negative effects.

The main streets of several Transylvanian villages were turned into Romania’s national roads, so now intense traffic runs directly through the center of these villages.

Unfortunately, the traffic completely changes the character of these villages, making it dangerous to cross the street, rattling the houses, spreading dirt constantly, and destroying the peace and tranquility.

Homes in these villages which were built long before the national roads were created now face directly onto heavy traffic.

Even though the village itself might be tiny, it’s actually difficult simply to enter and leave these homes because of the non-stop traffic hurtling past directly in front of the houses.

We found the villages which are directly crossed by national roads DN1, DN13, DN14, and DN15 are all horribly impacted.

There are many problems related to land titles and ownership in Transylvania. We were surprised at how often the ownership of properties was in dispute.

Each village has its own unique set of issues, but the most common causes we found included redistribution snafus during communism, corruption after communism, inaccurate land surveys, missing property deeds, thievery by local politicians, and intra-family feuds between relatives.

All this made us cautious, but since we only wanted to rent for a few months, it wasn’t such a worry for us.

But there are a lot of foreigners combing the area looking for real-estate deals, and a lot of locals have responded by trying to swindle them using dodgy documents and fraud.

So for anyone thinking about buying property in Transylvania, we’d suggest to be very careful and very thorough about all paperwork and legal issues.

In our case, looking to rent a furnished home in a village for a few months, the most realistic situations we found were houses where the owner was working abroad but planned on returning to Romania.

These were usually fully-functioning homes with electricity and running water. Many of them had large gardens, fruit trees, and fields.

Finding these homes was by word of mouth: just start asking around in a village, and within an hour the entire village will be helping out with the house hunt.

None of the homes we found were listed for rent anywhere official; it was all just informal talks with people who hadn’t planned on renting but were happy to earn extra money while abroad.

We weren’t the only foreigners living in houses in Transylvania this summer. In our travels through villages, we met Germans, English, Polish, and Spanish who had also rented (and in a few cases, purchased) homes in remote villages.

Some of the foreigners had connections to Romania: we met a few mixed couples, with one partner being Romanian and the other foreign, and we also met several Germans who had family roots in the area.

After exploring many villages and seeing many homes, we eventually found a house we liked in a remote section of a cute village.

Old architecture, an enormous garden and fruit trees, running water with hot water, electricity, internet, fairly clean and modern interior, fully furnished including kitchen.

There was only a dirt path, with no paved access road, to the neighbourhood, but we considered that a plus.

The owner was working in Germany for several months, so we dealt with his relatives in the village. We paid 450 eur per month (cash, in lei), including all utilities. That’s a bit higher than necessary.

I’d guess that we could have negotiated down to 350 eur, but we agreed on many extras which they provided, so we were happy with the deal. The owner’s relatives helped us with a lot and everything worked out wonderfully.

Village life in Romania

We fell in love with the countryside of Transylvania: the rolling hills, the forests, the views, the small villages, and the quiet, slow, rural life.

Old architectural styles. Horses and wagons. Fresh locally-grown produce. Pastors and their sheep. Fields of green and yellow stretching as far as the eye can see.

And the friendliest locals we’ve ever met in the world, always offering us cheese and jams and drinks.

Guidebooks and tourist sites describe the Transylvanian villages as a time bubble where locals live like the Europeans of centuries before, without modern inventions, industrialisation, or contact with the rest of the world. That’s definitely an exaggeration.

Mobile phone coverage is phenomenal in villages, much better than in rural areas of Western Europe, and almost every villager has a smartphone and is glued to it as much as urbanites.

Most villages, even in remote areas, have connections for electricity and phone/internet.

Although road quality can be poor, the area isn’t cut off: the vast majority of villages can be accessed by car, and from our experience, most extended families have at least one car, if not several.

We found that on average the Transylvanian villagers follow issues such as global economics and EU integration more closely than people we’ve met in small towns of the UK.

But although it’s not a true time warp, we found that many aspects of Transylvanian village life do indeed give it a feeling of old-style Europe.

The architecture of the majority of houses is the traditional Saxon style, with pastel-painted walls, small windows, and wooden crosses, which immediately gives the villages an old-time charm.

Access roads to many neighborhoods are often only by gravel paths or unpaved dirt trails through fields.

Many villagers use horse and wagon for transportation; in some areas, there are many more wagons than cars. Most villages have public wells which provide fresh water for everyone.

Sheep, goats, and cows graze everywhere under the watchful care of shepherds. Most families we know grow at least some food for their own use, and the majority keep chickens for eggs and meat.

Professional agricultural is very small-scale – mostly individual family farms, plus some operations run by small businesses or cooperatives – and there is very little of the large-scale industrial farming that exists in Western Europe.

And pristine, undeveloped nature surrounds all of it: fields and forests and rolling hills.

Village life in Transylvania isn’t for everyone. The pace of life is very slow. There are no tourist activities, no organized events, no museums or cultural centers.

There are no restaurants. There is no nightlife except for neighbours sitting outside their homes sharing food and drink.

For stores, there’s just a small mini-market in each village which has only the most basic food items; to buy anything else, you have to make a trip to the nearest city.

The economic status of the villages ranges from middle class down to very poor. In most cases, the more remote a village, the more poor its people.

The villages closer and better connected to cities are more middle class, as more of the residents work in the nearby cities at higher-paying jobs. But we found quite a few exceptions.

We found the villages to be extremely safe. Some friends of ours in the UK were horrified by our plan to live in a Romanian village and thought we’d certainly be robbed, murdered, or crucified (such is the effect of the Western European media’s stereotypes of Romanian villages).

For sure, petty robberies can happen; the cases we were told about were young teenagers trying to impress their friends, and one adult ne’er-do-well who got drunk and tried to steal from a neighbor. But overall, we found that there is little problem with crime.

The peace and quiet in the villages is wonderful. We are both academics, so we worked a lot on our projects.

With a great internet connection, we found it to be the best of all worlds while we worked: tranquility and nature ideal for focus and reflection, phenomenal internet for research and connection.

For us, village life was perfect: quiet, tranquil, slow-paced. We explored the nature by hiking through forests, biking through fields and over hills, and driving to the farthest areas.

We cooked. We worked in the garden. We worked on our projects. We got to know our neighbors. All in all, it was a perfect summer for us!

Shopping in Romanian villages

There aren’t a lot of shopping options in Romanian villages. The smallest villages have no stores at all.

In villages of at least several hundred people, there are usually one or two mini-market stores.

They sell a very limited selection of basic products: packaged meat, potatoes, tomatoes, maybe a few other fruits or vegetables, loaves of very basic bread, eggs, some canned vegetables, packaged biscuits and chocolate, cooking oil, cigarettes, alcohol, a few dairy products if they have a refrigerator, a few frozen products if they have a freezer.

We got a lot of food directly from the land where we lived. Many people have gardens with vegetables and fruits, so we often got fresh tomatoes, bell peppers, long beans, cucumbers, and cherries from our neighbors.

From shepherds in the area we purchased milk and cheese. Many people have chickens, so we were always able to get fresh eggs.

With fields of maize in every village, we had an unlimited supply of corn on the cob. We purchased honey from itinerant beekeepers who set up operations each summer in fields everywhere in Transylvania.

For any other food shopping, you’ll need to go to the closest city. The cities all have supermarkets and hypermarkets; Lidl, Kaufland, Carrefour, and Penny are the most common chains.

There are also old-style farmer markets in the cities, but they seem to be gradually dying, killed off by the cheaper prices which the big chains can offer.

Food prices

The high price of food was a common topic of conversation. Locals complained to us that food costs are too expensive relative to the average salaries in the area.

Workers who had spent time in Germany or Italy said they were surprised that food is not much cheaper in Romania than in Western Europe.

Young people, old people, all social classes: everyone was unified in their outrage about high food prices.

They told us that prices weren’t so high before and that it’s in the last few years that food has become so expensive.

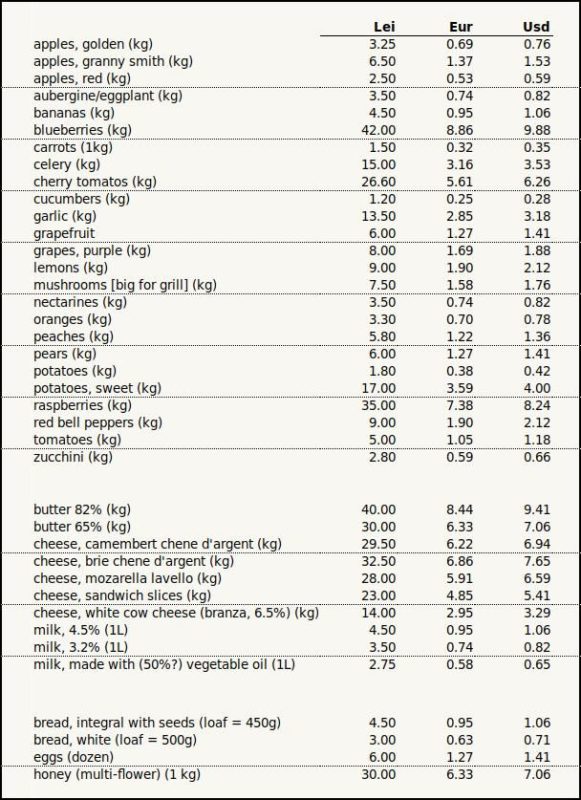

Making a price list is tricky, since prices vary from week to week and store to store, there are promotions, etc. So to keep it simple, for each product we tried to list the price which we found was the most normal and realistic over the summer.

We shopped mostly in hypermarkets in Făgăraș, with occasional trips to stores in Sibiu and Sighișoara. We didn’t find much difference in the prices between these cities.

On the other hand, there was a big difference between the cities and the villages. Except for locally-produced food such as long beans and eggs, the prices in the village mini-markets are higher for almost every product than the prices in the city hypermarkets.

We show the prices in euros and US dollars as well as lei, but to be clear, food in Romania is all priced in lei. For conversion to euros and US dollars in the table below, we used 1 eur = 4.74 and 1 usd = 4.25.

(Editor’s note: Please have in mind that the numbers below are 2019 data. I’d add around 20% – 25% more for actual prices, although some products on the list can still be found at similar prices)

Internet and mobile

The internet in Romania is incredible. It’s fast, cheap, and widespread.

Home internet is reliable and good value. Packages vary, of course, but we found that 15 eur per month was a pretty typical price for a home. Reliability is wonderful too: in our 3 months, we never lost internet.

We were often impressed to find great internet connections in the smallest of villages. For example, one village we visited is tiny and remote, with horrible access roads which are difficult to pass in the winter. But despite that, the village has great internet and mobile coverage.

As for mobile data, it’s a joy. Just walk into a telecom store, buy a sim card at a low price, and start using it.

No silliness like in some countries with passport registration, a long wait for activation, frustrating policies about number transfers or whatnot.

Just buy a card, put it in, and go. Packages change constantly and there are several competitors, so check around to find the best value for your needs.

In our case during the summer of 2019, we paid 13 euros a month for a package that has unlimited data at 10 Mbps speed, unlimited calls and SMS’s within Romania, and 500 minutes of international calls (plus 4 Gb of data in EU roaming, although we never used it so can’t verify how well it works).

Coverage reaches very remote areas, we rarely lost service in villages, we often had coverage even when traveling through hills and forests, and data speeds are very good at all times of the day.

Transportation

In most cases, you’ll need a car.

Transylvania is a big region, there are a lot of villages, and public transportation is limited, so getting around can be an issue. The main cities are well connected, and from those cities there are nice roads to most of the mid-size towns.

But the smallest villages are a different story. Reaching them can be slow because many of them have no real roads; instead, you go along poor access roads, dirt paths, unpaved lanes, and lots of mud and mini ponds. Heavy rain in particular can make transportation to these remote villages difficult.

Walking around in Transylvania

Walking isn’t realistic for most purposes. Transylvania is too big and spread out to explore by foot.

Hiking the trails and forests is fun, but there’s no way to cover the whole area on foot.

Even within villages, walking can be tough: some villages are tiny in population but are so spread out, crisscrossed by farmland, that it’s quite a journey to walk from one end to the other.

Biking in Transylvania

We initially hoped to only use bicycles for getting around. The paved roads between the major cities and mid-sized towns are easy for bicycles. The dirt roads between the smaller villages can be rough in cars, but they’re great fun with bicycles.

And with bicycles, you can go where cars can’t: through the forests and over the hills. There are very well-marked bike paths you can use to cut directly from one village to another without needing to pass back and forth through the bigger towns in the region (more on that in the section Biking and hiking).

A nice plus is that most of the area is flat with only small rolling hills. So you could certainly explore all of Transylvania on bicycle, and we met a few hardy foreigners who do just that.

But we realized that for us, bicycles are good for day-trips to explore the forests and backtrails, but not realistic for daily life and definitely not for exploring the whole region.

The area is too big: 30km rides one after another are too much for us, especially as we learned that the terrain is much steeper than we expected (it’s mostly flat overall, but the roads go up and down the rolling hills quite a bit, and if you come close to the looming mountains, it’s a big climb).

Plus, some of the roads are too narrow and have too much traffic to be comfortable for cycling.

Thanks to very poor urban planning, these small village paths were designated as the country’s national roads in the area, but weren’t widened to handle the heavy traffic.

These roads are horrible for bike riders because they’re small, busy, and have no room for a proper bike lane.

We found it very unpleasant and rather dangerous to ride a bike on these narrow highway streets while cars constantly speed past just a meter to our side. Unfortunately, on many routes there’s no way to avoid these roads.

Public transportation in Transylvania

Public transportation is very limited outside the main cities. There are bus routes and private minivans between the major towns, but they run infrequently.

Also, the routes only stop in the bigger towns on the main roads, so you’ll be walking a lot from the bus stops to reach the many tiny villages which are at the end of small dirt lanes.

Hitchhiking in Transylvania

Hitchhiking is a fun possibility. Romania is great for hitchhiking. It’s very much part of the culture.

We hitched a few times and loved it. On the main streets between principal towns, we never had to wait more than a few minutes for a ride.

Although the wait on smaller village roads was longer because there’s little traffic in the remote regions, the drivers in those areas were even more helpful than on the main roads: the first car we saw when hitchhiking in a remote area almost always stopped to pick us up.

As for money, we tried to pay the driver every time, and every time the driver refused.

But we found that although occasional hitchhiking is fun, you can’t count on it as a long-term, reliable transportation option if you’re living in the region.

Many of the village roads are empty for hours at a time, so even though people are very helpful, there just isn’t enough traffic for you to rely on (in quite a few of these areas, you see many times more horses and wagons than cars!).

So for us, having our own car was the only realistic option.

Do you need to learn Romanian to live in a village in Transylvania?

In the big cities of Romania, many people speak very good English, plus often German, Spanish, or Italian.

In the villages, though, almost no one speaks English. We expected that middle-age people and older adults wouldn’t know any English.

But young people’s knowledge is just as bad: we found that although English is usually compulsory in school, most young people in the villages don’t know much more of the language than the numbers (and even the numbers might be a stretch in many cases).

It’s a reflection of the poor education offered in these areas, and it’s especially sad because it really limits the local people in their future job prospects.

But as a foreigner in Transylvanian villages, it’s not all bad news about the language. We found a few bright spots in the situation.

First, it’s not so hard to reach basic proficiency in Romanian if you already know another Romance language.

For sure, Romanian is harder than the other Romance languages, but it’s not as tough as, say, a Slavic language.

About 60% of Romanian vocabulary is from Romance sources (mostly either inherited from Latin or adopted more recently from French), so that gives you a very large base of words you can pick up quickly. In our case, we already knew French and Italian.

Unfortunately, it won’t be as easy as that if you don’t know another Romance language.

If your only language is English, then to reach a basic level of comfortable Romanian proficiency, I’d estimate that you’d probably need to invest 3-4 times the amount of time we did.

Another big bright spot in the language situation is the high percentage of Romanians who have worked abroad.

Every person we met in a village in Transylvania had either personally worked abroad or had a close family member who had.

In a few cases, the Romanians who worked abroad had picked up a bit of the language: usually German, sometimes Italian or Spanish. We found that their language experience is not much of a direct advantage.

Their knowledge of the language is very low, since when abroad they’re usually manual laborers and surrounded by other Romanians, so their skills rarely help you to communicate as a foreigner in their villages.

Instead, the advantage is indirect: we found that the experience of having working abroad has made the local people extremely patient and understanding about language difficulties.

When trying to communicate with someone who barely speaks your language, most people in most countries of the world quickly become tired and just give up.

But in Romanian villages, we found that people really want to communicate. Their sympathy towards foreigners is palpable: they’re used to being in a foreign country themselves and having problems communicating, so when they’re in the reverse situation in their own country, they are extremely accommodating about language difficulties.

They’re willing to spend huge amounts of time to have a conversation using any way possible: phone/internet translators, hand gestures, writing on paper, dictionaries, pictures.

The upshot? Almost no one in the villages speaks English or any other language, so the more Romanian you can learn, the better.

But thanks to the empathy gained from suffering language problems themselves when they’ve worked abroad, as well as their cultural tradition of being kind hosts, the Romanians you meet in villages will really try hard to communicate with you despite any language barriers.

Information on small towns in Romania is limited

Romania has always fascinated us, so we decided we wanted to spend a long summer break of several months exploring the country’s nature and culture.

We didn’t want to travel around at a frenetic pace, staying in guesthouses or hotels night after night. We also aren’t interested in organized tours.

Instead, we wanted to find a home where we could live comfortably, get to know the neighbors, and independently explore the area at our leisure.

We weren’t sure where we wanted to stay. We wanted to live in a small town or village surrounded by wonderful nature, but there are thousands of potential places in Romania, so it was hard to know where to start.

We decided to narrow our focus to the Transylvania region because of the beauty of the nature, the traditional architecture, and the rural village life, but that still left hundreds of options.

We researched a lot before leaving to Romania. There are many great resources: travel guides, blog posts, reddit/r/romania, Google Maps street views, and the wonderful website Romania Experience.

But even with all that, we found that it was still hard to get good information about the villages.

When we arrived, we learned what the problem is. Information on the internet is very useful and accurate about the main cities in Transylvania: Sibiu, Brașov, and Cluj are very well covered.

Even for the small- to mid-sized cities like Târgu Mureș, Mediaș, and Sighișoara, there’s good information available online.

But it turns out that for the small towns and the countless little villages, there’s very little information on the internet and the scant information which does exist is often not correct.

Many places have no maps, no recent pictures, no demographic information. We found several cases where maps exist but are wrong and pictures are mislabeled or attributed to wrong areas.

Most importantly, we found that each village has very unique characteristics which are vital to know, but which you can’t learn on the internet: the condition of the houses, the availability of water, the state of the roads, the level of inhabitedness vs. abandonment, the ratio of cars vs. horse-and-wagons, the level of dire poverty, etc.

The villages vary massively from each other in these characteristics. Many of the villages turned out to be very different in reality – sometimes better, sometimes worse – from what we had anticipated based on internet research.

I imagine that some day in the future, you’ll be able to research online about these villages. But we learned that at least for now, the only way to get real information is to go there and investigate yourself.

Wrapping up

Angela covered everything that had to be covered about living in a village in Transylvania, just as promised and I really loved reading about her experiences, the friendliness of locals and the fact that it’s actually not that difficult to live in a remote place, in a small village, somewhere in Transylvania.

- Beach, Please Festival 2024: Lineup, Schedule & Dates - April 19, 2024

- Best Music Festivals in Romania – with Dates & Lineups [2024 Update] - April 17, 2024

- Visiting the Peles Castle in Romania: Everything You Need to Know - April 11, 2024

Wow! Brave souls in my book. I read this with interest as l could never imagine living in a sleepy town like they did. I think l would go crazy :-). My parents hail from a tiny village much as she described and when we used to visit for Christmas, I would be looking forward to leaving after two days max, we all were. I’m not surprised about the animal abuse though. It’s a way of life in most parts of the world, some parts of Nigeria included. The pictures are wonderful and really give you a sense of the tranquility. Thanks for sharing.

I agree that this is not something that anyone could do: I sometimes find myself dreaming about the slow paced life, soaking in the fresh air and the nature and the tranquility and other times I think I’d go crazy with that. The hikes and nearby trips make everything more exciting though, so at least for shorter terms, I think it could be really enjoyable.

Thank you for sharing, Angela. This was fascinating to read about my country. Though the tranquility does not scare me and the friendliness is inviting, the cruelty towards animals and the fact that good hospitals are probably too hard to reach when it’s an emergency would probably put me off. Brave of you to take such an adventure, and happy you did so and shared it with us. We hope you’ll visit us again soon.

This was a very good read and brought back many memories of the time I had spent in a few small Romanian villages. I was last there in 2003, so I see a few things have changed for the better (cellular phone and Internet coverage), some things have stayed the same (the dangerous sheep dogs and bad roads) and other things like higher food prices have gone in the wrong direction. I didn’t have so much luck with corn on the cob. In my village, they grew a hard variety that wouldn’t soften up no matter how much I cooked it. I think they ground it down for corn meal or fed it to their cows. The friendliness of the locals also hasn’t change, I am glad to hear. I can still remember the taste of that fresh cheese, the vegetables, the delicious bread, the honey, the eggs, the homemade wine; all the flavors seemed so much more intense. Maybe it also had to do with the increased physical activity of village life. Everything tastes better when you are hungry!

While roads in Romania are generally bad, I’ve seen some improvements in the past few years, even with roads leading to villages: more and more are getting the asphalt treatment (mostly thanks to the EU funds), so things have improved slightly compared to 10 years or more ago. But overall, the quality of roads – and especially the number of dirt roads or stone roads is scary.

Well said about the food tasting better when you’re hungry. The fresh air probably has an effect as well: I always seem to eat better when visiting our village house as well (and it’s usually food we bring back from home). But that clean air… yum! :))

Romania Experience:

Loved the picture of the guy chillin’ on his dray! Looks like he hasn’t a care in the world;-)

I’m afraid it’s all too rustic for me and my city sensibility. Still, the people seem mostly content,

which is all anyone can ask for these days. ~Teil

Yes, the pace of life is definitely in a different gear there. People work really hard, but they also seem to take everything slower than people do in the cities. That’s something I always liked about the village life!

Exceptionally well-written and informative. Thank you, Angela!

Wonderful article, reminds me of the “Romania through their eyes” series… Also rejuvenates my desire to move out of the capital city and into the whatever is left of the untamed land.

I feel compelled to address the gypsy issue; it is usually Romanians who are discriminated by the authorities, not the other way around. This ethnicity is so profoundly ant-social… can’t wait to get out of their new power base in Tiganestii Noi neighbourhood of Bucharest.

P.S. I (we ) aren’t just a bunch of racists; here is an article on people form the same village as I have living across the street: https://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/village-in-romania-makes-exodus-to-troubled-berlin-neighborhood-a-825933.html

Superb article. Precise, detailed information with many specific points. Very well-written.

I don’t see many such helpful guides offered for free on the internet anymore by a (de facto) anonymous person. Travel blogs, Instagram guides, and YouTube channels tend towards self-centered self promotion and superficial banal overviews of the location without detailed, well-researched information.

My boyfriend and I were planning a trip last year to live the summer in Transylvania. Covid stopped us, obviously. So we’re considering it again for this year. We’ll see how restrictions look, but if nothing gets worse, we think we should be able to go at the beginning of July.

This guide has become our bible for planning our trip. And the pictures are amazing; so tranquil, so enchanting, they give us motivation to go.

So a big big thanks from us for publishing it!

Indeed, Angela wrote an amazing and complete guide. I am happy to hear that it helps you put things together and plan your next adventure. I am sure that there will be minimal (if any) restrictions in July, so you will be able to visit Transylvania and hopefully fall in love with it.

thank you so much!

i’m going to transilbenia in a week, but using only public transportation..

do you have any rout recommandation or tips/guidelines for traveling with trains

and buses only?

Unfortunately, no recommendations – there are many possible routes and it depends a lot on where you start and what you want to see. Enjoy the experience, though!